I have a love/hate relationship with the Salem Witch Trials in pop culture. Sometimes, the 1692 trials appear in an appropriate context albeit littered with inaccuracies, like Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, and sometimes it’s just terrible, like WGN America’s Salem. Marvel is a bit of a mixed bag since the 1976 comic with Spider-Man fighting Rev. Cotton Mather is a hilarious concept but historically extremely wrong. The new series Agatha All Along has some history sins related to Salem, but I also find one of the plot devices incredibly fascinating in a historical context. A key plot point (as of episode 4) is a sigil to stop the character Teen, played by Joe Locke, from revealing his identity to Agatha, portrayed by Kathryn Hahn. Whenever Teen discusses his name and background, Agatha and the other witches are unable to hear it. In some instances, Teen speaks, and a sigil covers his mouth with a W or M. In another scene, Teen discusses his background, and Agatha cannot hear his voice while other sounds are clear. This sort of sensory bewitchment during the Salem Witchcraft Trials is a significant part of my dissertation research.

The show’s context: There is a character named Teen who sought out the witch Agatha Harkness to go down the Witches’ Road. Teen is an unnamed teenager and his parentage, background, supernatural abilities, etc are all questions that will presumably be answered over the season (yes, I have seen the fan theories). Agatha initially asked Teen for his name, and the sigil appeared over his mouth. Later, Teen discussed his background in the car with Agatha who sees that Teen is speaking but cannot hear him despite hearing music from the car’s radio. In the third episode, the group of witches ask for Teen’s name and the mysterious letter covered his mouth again, preventing all of them from hearing it.

Early American Disability context: Historical disability is a tricky subject since our contemporary understanding of disability, as a collective term for various kinds of bodies and embodiments, does not have a direct parallel in the early modern period. People with disabilities of all sorts have always existed, but the societal and environmental constructs that determine disability change. To study historical disability, I look for moments where a body is treated as, discussed as, or indicated as physically, cognitively, or sensorially different. In all time periods, there are imaginary expectations of an able body, and while no body is perfectly able in all ways, certain bodily conditions are considered deviations from this imagined norm and socially constructed as disability. For example, in the modern day, most people do not think of wearing glasses as a disability. This is contextual for someone with the healthcare and socioeconomic position to visit an optometrist and purchase glasses, but in the zeitgeist, glasses are not really treated as a social barrier. In a different period, the same visual condition might not have an easily accessible form glasses, and therefore societal expectations about vision, such as ability to read or travel via visual cues, would be a disability and treated as such. It could also be that a person ages into a disability and loses their vision over their time. An act could occur where a person loses eyesight, or a medical procedure could restore eyesight, meaning their disability status changes. The long story short here is that disability is extremely contextual, and so I look at how forms of bodily and embodied difference effect historical actors, rather than seek out historical actors who identify as disabled or identify with a disability aligned with a modern parallel.

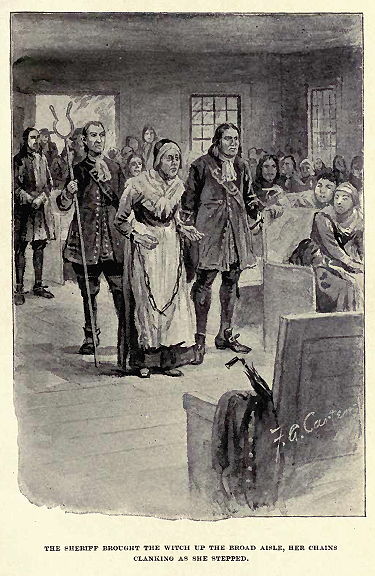

Throughout the Salem Witch Trials, accusers utilized temporary disabilities to make accusations of witchcraft. Frequently, accusers claimed sensory afflictions prevented the accusers from providing testimony, but it also posed a threat. When Susannah Sheldon testified against several accused suspects, she said “they made me deaf and dumb and blind all night” as part of their supernatural harm to encourage Sheldon to sign the devil’s book and surrender her soul. Elizabeth Reis’ scholarship on gender and the soul discusses how Puritan theology included expectations that a strong body protected the soul, and Satan sent witches to harm physical bodies to force the submission of an individual’s supernatural soul. In short, witches harmed the body before harming the soul, but the body also served as an intermediary for the soul’s religious experience in the physical world. People listened to sermons, spoke prayers, and read the Bible, meaning sensory disability cut off the soul from religious participation. Witchcraft afflictions preyed upon this interplay between the visible world and invisible world, between the body and soul, through disability. Throughout the witch trials, this understanding of disability consistently shaped the course of events.

Tituba’s confession was one of the clearest influences of disability. The first accusations in February resulted in three arrests. Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne, and Tituba are often called “the likely suspects” as women whose social standings and reputations made them easier targets to the Puritan witch hunters. Good, a beggar; Osborne, a woman with a scandalous past; and Tituba, an enslaved Indigenous woman, represented threats to Puritan social hierarchy that prized evidence of God’s blessings, like wealth; strict morals, ability, and whiteness. When the accusers named these women, they (or their parents) probably knew the accusations were believable. Early successful accusations would likely lead to opportunities to name more suspects; a slew of historiography discusses the various motivations that could have been at play. On March 1, 1692, the three women appeared before magistrates for examinations where Good and Osborne denied the charges. Tituba confessed.

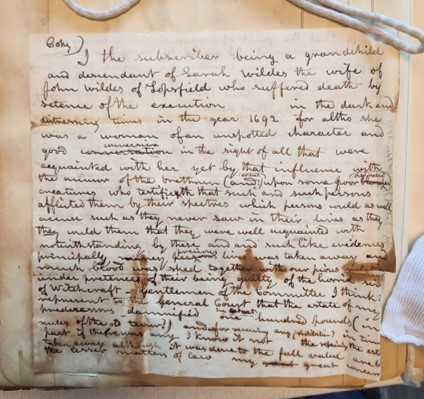

Tituba’s confession affirmed the accusations, and she also named Good and Osborne as fellow conspirators with Satan. Within the confession, Tituba executed careful control of the narrative of her confession and disability. She discussed how the devil appeared to her, how Good and Osborne forced her to harm the accusing children, and she said others already signed the devil’s book, meaning the authorities could pursue more witches. Rev. John Hale of a neighboring town described that Tituba’s credibility partially came from her recollection of answers and that “She became a sufferer herself.” Tituba experienced afflictions during her confession and as the magistrates questioned her. She described that Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne attacked her, and their specters “would not let her see & after that [she] was once or twice taken dumb herself.” Tituba lost both her speech and sight during her confession. Her credibility came from repeating answers and experiencing disability, but when properly executed, her moments of temporary disability occurred according to the questions that Tituba did or did not want to answer. She decided when to reply to the magistrates. The transcript of her examination ended after she lost her physical senses, like speech.

In another example, after Samuel Wardwell was found guilty by the Court of Oyer and Terminer, Wardwell spoke to proclaim his innocence ahead of his execution. However, as he protested his conviction, reports say that smoke from the executioner’s tobacco pope blew into Wardwell’s face and interrupted his speech. According to Robert Calef’s critical account of the trials, “those accusers said, the Devil [hindered] him with smoke.” During the examination of Rebecca Nurse, Rev. Deodat Lawson reported that “The afflicted persons said, the Black Man [the Devil], whispered to her in the Assembly, and therefore she could not hear what the Magistrates said unto her.” In both instances, a supernatural force exerted power over a person’s physical senses. For Wardwell and Nurse, these moments proved their affiliation with Satan while court authorities used Tituba’s loses of speech and sight to prove the veracity of her confession. A fluid interpretation of disability that benefited the accusations was a throughline of the entire witchcraft crisis.

Agatha All Along uses this same theme of witchcraft and sensory disability- in both Teen’s inability to audibly speak or Agatha’s ability to hear him speak. I don’t know if the Marvel Universe knowingly drew on historical forms of witchcraft afflictions to influence the senses, but it references a history of disability and witchcraft. As much as Agatha’s relationship with the Salem Seven commits many historical sins, the sigil as a form of disabling bewitchment is an accurate portrayal of how witches were alleged to harm victims. It also speaks to the history of ablism that tied certain embodied differences to the devil and framed disability as moral judgement. Teen shows the historical beliefs, but how the sigil further plays out and whether it offers a critique to ablism in witchcraft remains to be seen. My dissertation work digs deeper into the Salem Witch Trials, Puritanism, and disability history with a much longer discussion on Rebecca Nurse and her accusers, so wait a few months for final chapter drafts.

Select Bibliography

For the Salem court records, see salem.lib.virginia.edu

“He that Hath an Ear to Hear”: Deaf America and the Second Great Awakening” by Sari Altschuler, Disability Studies Quarterly Vol. 31 No. 1

More Wonders of the Invisible World by Robert Calef

A Modest Enquiry into the Nature of Witchcraft by Rev. John Hale

Damned Women: Sinners and Witch in Puritan New England by Elizabeth Reis

Disability Theory by Tobin Seibers