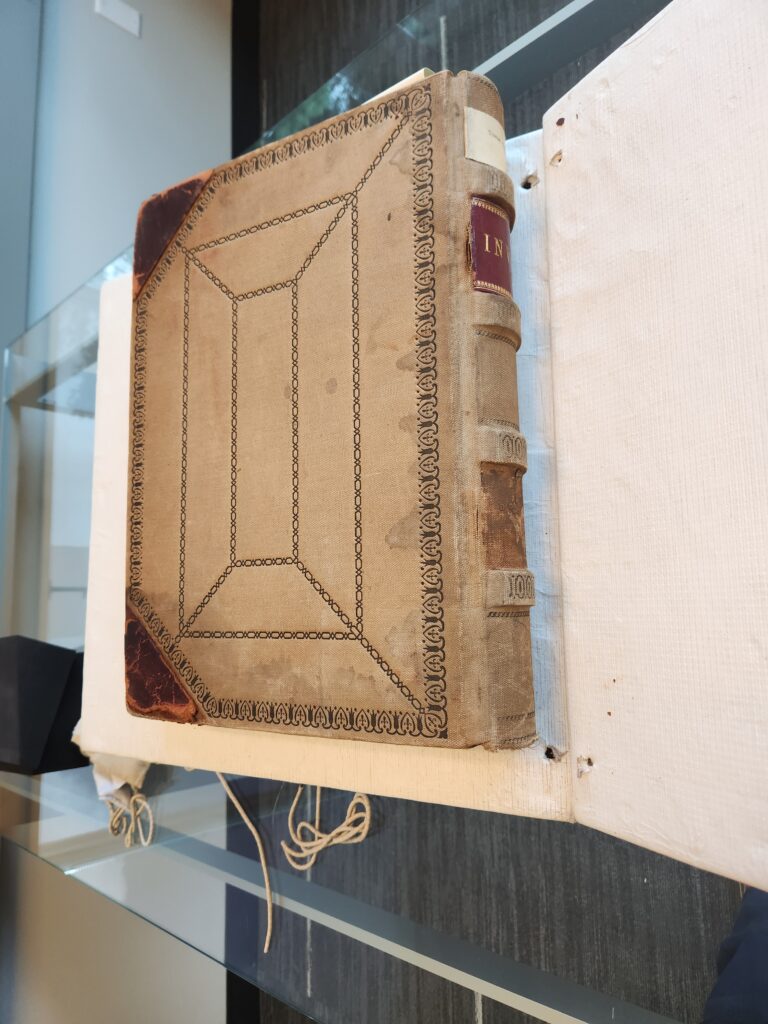

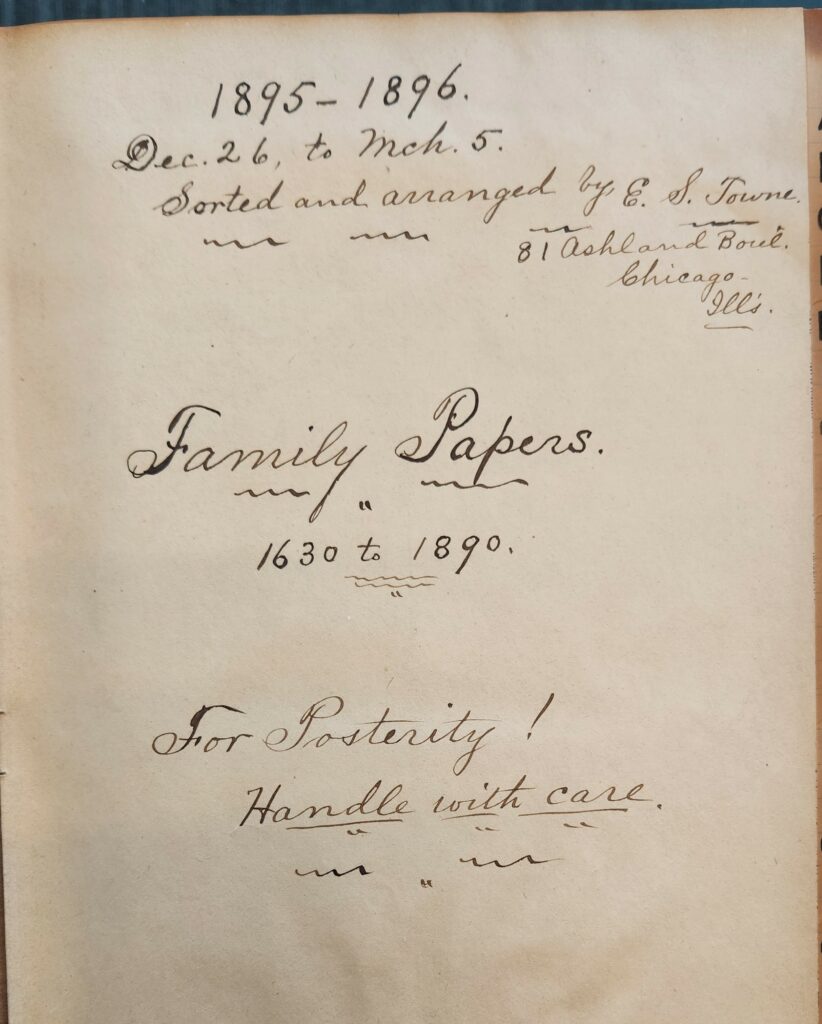

I am spending this summer at several archives with funding from the New England Regional Fellowship Consortium to research for my dissertation on early American disability history. I am currently at The Phillips Library in Rowley, MA, to look at several collections related to my project and ended up finding something exciting. Last week I viewed the Towne Family Papers: a collection of documents related to a large and prominent Topsfield, MA, family with contents dating from 1630 to 1928. Boxes 4 and 5 contained a two-volume scrapbook with family papers from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries compiled by Edward Stone Towne.

As I flipped through the books, the contents seemed eclectic: stamp and currency collections, seventeenth century land deeds, hand drawn maps, sermon notebooks, genealogy notes, and more glued to the pages of this massive tome. Then I found something that stunned me for a moment. The volumes both go chronologically through the centuries and the piece of paper on this next page was out of place between documents from the 1730s. Although I’m not an expert on paper or handwriting, I knew this page was most likely from the nineteenth century and therefore not in chronological order. Then I started to read it to see why Edward Towne changed his organization.

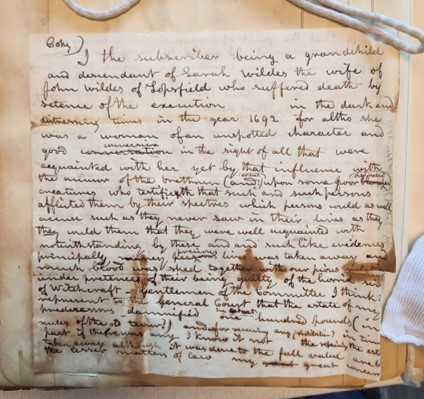

Copy)

I the subscriber being a grandchild and descendant of Sarah Wildes

My heart skipped a beat. Sarah Wildes hanged on July 19, 1692, for the crime of witchcraft. I skimmed over the document to try and figure out what this was and thought it was odd I didn’t recognize it. I started to research the Salem Witch Trials for a high school project in 2011, my undergraduate thesis at GWU was a network analysis of the trials, and my graduate work at GMU has a significant amount of Salem related history. I just taught a digital history course themed around the trials. Chapter 1 of my dissertation looks at the role of disability during the witch trials and now my second chapter outline has started to include more of the post-witch trials petitions and historical memory of the descendants. In other words, I’ve read the court records many times and this document fit the scope of my current research, but why didn’t I recognize it? I just looked at a the family petitions after the witch trials again and a grandchild petitioning for Sarah Wildes didn’t ring a bell. Then I flipped it over.

Pet. of John Wildes 1739

I spent the spring semester assigning my students primary source readings from the UVA Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project and the documents didn’t really go this far into the eighteenth century. There are a few outliers but the efforts to receive restitution occurred around 1710. Not only is this petition much later, I remembered seeing that Sarah’s son Ephraim (John’s father) sought restitution around that time too, so why a second Wildes family petition? I checked the UVA database to see if this document was listed anywhere. I search Sarah Wildes’ case file, the index for her son Ephraim, and the only John Wildes listed is in reference to her husband. Then I asked to look at the reading room’s copy of Rosenthal’s Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt and again, no petition of John Wildes.

When I went home for the day, I carried on the search. I checked the UVA database again, followed all the links to other repositories, searched Margo Burns’ website, checked all 34 volumes of the The Historical Collections of the Topsfield Historical Society, and also just searched on Google. I could not find this document anywhere. I also reached out to Emerson Baker, a professor at Salem State who I interviewed in 2011 for my high school National History Day project; and Margo Burns, the project manager for Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt. If anyone knew about this document: it would be either of them. Baker pointed me towards a late 1730s legislative effort to pay reparations to families impacted by the witch trials as a reason for such a document to exist. Burns offered points of skepticism: the £100 request is high and also odd given Ephraim Wildes sought and received £14 in 1711, the petition refers to Sarah Wildes’ estate but she wasn’t a widow so the estate wouldn’t be considered Sarah’s, and a number of dramatize/romanticized/fictionalized tales of the witch trials came out of the nineteenth century so it could be made up. There is no known original document to provide a better context. In summary, this is an odd find.

I spent some time digging, and while I remain cautious about the legitimacy of the text, I think it offers a true transcription of a petition created by descendant of the witch trials, and I’ll present the case here.

- Its a weird choice to fake

Given the other pieces of evidence that I’ll share below, I trust my initial instinct is that this is a weird choice of document to create for some ulterior motive in the nineteenth century. Why a copy of a petition from nearly 50 years after 1692 the for your family scrapbook and not a document more related to the actual witch trials? Why include so many transcription second guesses and quirks? The books are filled with documents from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and only one related to the witch trials on clearly newer paper labeled “Copy”. Its obviously not original and not like the other documents so its a strange effort to fake in a family scrapbook. This is a not-so-historical or scientific rationale, but Edward Towne wrote “For Posterity!” on the inside cover and otherwise took great care to present centuries of family history. Is this tangential document to 1692 really how he’d sneak in a piece of fiction? - Timing

The text of the document fits perfectly into the timeline of Massachusetts legislative efforts to pay restitution for the witch trials. In December 1738, the House of Representatives voted “That Major Sewall, Mr. Fairfield, Mr. Norton, and Mr. Danforth, be a Committee to get the best Information they can into the Circumstances of the Persons and Families who suffered in the Calamity of the Times in or about the Year 1692, and have not received any Restitution or Reparation for their Losses and Misfortunes, that the Committee lay the same before the Court as soon as may be.” The John Wildes petition addressed to a committee seeking restitution is dated just a few months later on May 28, 1739. The date coincides with the start of the a legislative session on May 30, 1739. There are few records about the Committee even forming, let alone their business, but a couple months to start up and ]for descendants to prepare materials is a reasonable timeline. - John’s word choices

I think John Wildes took inspiration from Rev. Israel Loring’s 1737 election day sermon given before the House of Representatives. It is also likely that any political movements led by descendants used the language first and Loring took inspiration from them. Either way, in this chicken or the egg question, we have both the chicken and the egg to see how Loring and Wildes represent the reparations movement.

Loring blatantly asked the legislators to consider paying restitution to descendants: “Whether there is not a great Duty lying upon us, respecting the Transactions of the Year 1692, when not only many Persons were taken off by the Hand of publick Justice for the supposed Crime of Witchcraft; but their Estates also ruined, and their Families impoverished…Now tho’ the loss of Parents cannot be made up to their surviving Posterity, yet their Estates may; And the Question is (if it be not beyond all Question) whether a Restitution is not due from the Publick to them…Hereby Infamy may be taken off from the Names and Memory of such as were Executed, and who it may be did not in the least deserve it.”

Maybe John read a copy of the sermon two years later while preparing his petition or perhaps Loring and Wildes both represent a broader trend, but the 1739 petition fits in with this phrasing. Loring refers to repairing the estates of victims and removing the infamy of the names and memories of the accused suspects. Both points appear in the Wildes petition. John asked about “cause to (take?) off the scandal in some measure and also make (restitution or Restoration?) as to damages in my predecessors estate at that time.” If John parroted the talking points of a printed sermon or Loring conveyed the arguments of a movement, either case explains why the petition refers to Sarah Wildes’ estate which would have been an inaccurate description of her property at the time of her execution. - The Towne family’s genealogy

The scrapbook by Edward Stone Towne covers a long period of the family’s history and while link the Wildes family is not immediately clear since the petition is the only overt reference to the surname, the petition and scrapbook seem disconnected. However, The Descendants of William Towne clears up the mystery for why Edward had a copy of a 1739 petition regarding Sarah Wildes’ estate. Edward’s father Ezra (1807-1899) is the son of Jacob (1768-1736) who is the son of Jacob (1728-1768) who is the son of Benjamin (1691-1782) and Susannah Towne. Susannah is the daughter of Ephraim and Mary (Howlett) Wildes and therefore the sister of John Wildes and Sarah’s granddaughter. Although Susannah died in 1736, years before John wrote the petition, the link between the Townes and Wildes families is clearly established. The petition possibly changed hands on the family line or Edward (or another Towne) copied it from the Wildes side of their family and passed the transcript down. It isn’t a stretch to see why the scrapbook contains such a document. There are a couple other marriages between the Wildes and Towne families over the two-hundred years between the witch trials and the creation of the scrapbook. The link to Susannah is just the most direct between Edward and John Wildes although the petition (and/or copies) may have travelled along other lines, but nevertheless, it has some degree of provenance.

There are several other indications that the text of the document is legitimate, but I want to move on and address the prior reparations given to the Wildes family and why this petition matters. In 1710, Sarah’s son Ephraim filed a petition for £20 and received £14. Other families did received more: according to one order of payment, George Jacobs Sr.’s family received £79, Geoge Burroughs’ family received £50, and John Procter’s family and Elizabeth Procter received £150. Yes, the £100 requested by John Wildes is comparatively high. As a grandson rather than a child of a victim and as a member of a family that already received payment, his petition might have been a longshot. There are no similar records for this committee’s work and the payments sought by other families or the success of those 1730s petitions so we can’t tell much based on the amount requested. Maybe it wasn’t considered unusual for this committee. Maybe John figured he’d give it a try, maybe it was greed, or maybe or maybe his family did still ache from the trauma of the witch trials even nearly fifty years later. We don’t know, but I think Ephraim’s petition helps make sense of it.

Ephraim began by mentioning the fees his family had to pay for his mother’s time in both the Salem and Boston jails, but he went on to a more emotional cost.

Besides either my father or myself went once a week to see how she did and what she wanted and sometimes twice a week which was a great cost and damage to our estate. My father would often say that the cost and damage we sustained in our estate was twenty pounds and I am in the mind he spoke less than it was: besides the loss of so dear a friend which cannot be made up.

John Wildes was two years old when his grandmother hanged for witchcraft. His father finally received restitution when John was twenty-one years old. He spent his entire childhood with Sarah’s death in the background and his father persisting in a quest for compensation. Whatever stories Ephraim or his grandfather John told about Sarah and their visits to the prison, whatever accounts of the trials, and whatever frustrations they vented in the battle for reparations, the pain of the witch trials’ legacy surrounded John for decades. When the opportunity arose later to fight the damages done to his family by the witchcraft accusations, why wouldn’t John leap at the chance? When he wrote “my great concern is the guilt of innocent blood may not rest on our land” he eschewed the monetary compensations and instead leaned on the narratives of the injustices that he watched his father fight and win in some small part. Nothing could replace the loss of a wife, a mother, a grandmother, a dear friend like Sarah. The trauma of the witch trials lingered over John and his family so much that forty-seven years later, the Wildes family continued to seek justice.

This is not the original document, and maybe now with the text uncovered the source may be located by revealing some way to look for it. Whether an archive’s catalog just lists “Wildes, John” or “1730s legislative petitions,” there are possibilities. Maybe someone else out there has seen this document before and it isn’t online or someone will spot it someday. In any case, it appears that the text of this document has never before been connected to any of the efforts to transcribe the Salem Witch Trials court records and it offers something new about the personal tolls afflicted on the families of the victims. There aren’t many petitions like this one that survived in any form, and less so after the 1710-12 restitution process. The committee’s work in the 1730s must have yielded dozens of similar sources that no longer exist or are yet to be associated with the Salem records. Even as this petition is merely the text of a document and not the document itself, it is a new Salem Witch Trials document.

My best effort at transcribing the entire document:

Copy)

I the subscriber being a grandchild

and descendant of Sarah Wildes the wife of

John Wildes of Topsfield who suffered death by

setence of the execution in the dark and

distressing times in the year 1692 for altho she

was a woman of an unspotted character and

good

conversationconversion in the sight of all that wereacquainted with her yet by that influence with

the [illegible] of the brethren (and? or how) upon some poor deluded

bloodedcreatures who testifieth that such and such persons

afflicted them by their spectres which persons could as well

accuse such as they never saw in their lives as they

they could them that they were well acquainted with

notwithstanding by these and and such like evidences

principally many

personsprecious lives was taken away andmuch blood was shed together with our pious relative

under pretense of their being guilty of the horrid sin

of Witchcraft- Gentlemen of the Committee I think to

represent to the General Court that the estate of my

predecessors [=demised?] is at least are one hundred pounds) in

rules of the old tener?) and of our receiving any (restitution? in time

past if there was any I know it not the repairing the estate

taken away although it was done to the full value are but

the lesser matters of law my

greatgreat concern[Reverse] is that the guilt of innocent blood may not

rest on our land I would be very far from

reflecting on those worthy men which then sate

in the seat of judgement but it tis (too or so?) plain

for any to deny but that they were strangely

misguided in that dark time so gentlemen

of the Committee I rest the whole of the difficulties

above (named or mentioned?) with you hoping you will give it due weight

in having a (very?) deep thought upon them dark and

sorrowful times so as the great and general Court

may may see cause to (take?) off the scandal in

some measure and also may (restitution or Restoration?) as to

damages in my predecessors estate at that time

so gentlemen I am yours to serve who am in

duty bound shall every pray

Dated May ye 28 day 1739- John Wildes

[Reverse left margin: Copy- Pet. Of John Wildes 1739-]

Thanks to Emerson Baker and Margo Burns for their comments on the document as well as the Phillips Library archivists and staff!